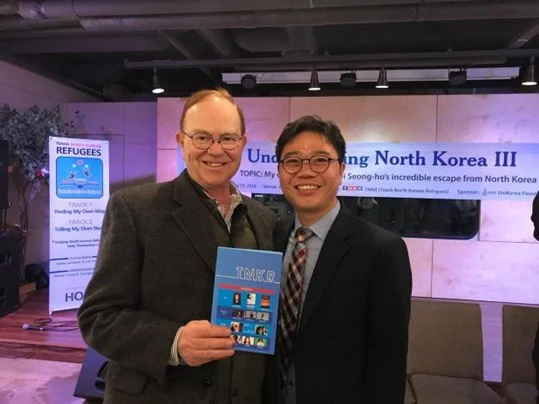

History of Korea, Part 9

by Michael Downey

photo credit: Michael Downey

The final days of the Joseon Dynasty were marked by chaos. Koreans often describe their history as that of a small, righteous nation trapped between several large, hungry tigers. This image aptly describes Korea’s situation at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries. The two primary tigers were China and Japan.

Both nations had long histories of preying upon weaker neighbors. Korea may have been both weak and politically naïve. As the “younger brother” to imperial China, Korea remained locked in a tributary relationship. Meanwhile, Japan was on the rise—defeating China in the Sino-Japanese War and Russia in the Russo-Japanese War. Japan’s victory over a major European power filled it with confidence and ambition.

Japan set its sights on the rest of Asia through its vision of a Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Its principal rival was China. Both shared imperial ambitions. China had long viewed itself as the “Middle Kingdom,” expecting allegiance and tribute from surrounding nations. Japan, newly empowered, was ready to replace European colonial powers as Asia’s dominant imperial force.

Korea was Japan’s first target.

Japan had long cast covetous eyes on the peninsula. The Yamato state traded with, borrowed from, and eventually plundered the early Gaya Confederacy—later claiming it as a colony. As Japan’s internal politics evolved, Korea suffered repeated attacks from Japanese pirates known as Wako, which were resisted by both the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties.

In 1592, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of Korea. The invasion was eventually repelled with significant assistance from Ming Dynasty forces. As a tributary state, China was obligated to help Korea and grew accustomed to intervening militarily. It became convenient to station troops permanently in Korea. When Japan invaded again in 1596, Korea—better prepared and supported by Chinese forces—repelled the invasion more quickly. Japanese ambitions to conquer China consistently involved first controlling Korea as a land bridge.

In 1894, when the Tonghak Rebellion threatened Seoul, Korea again called on the Qing Dynasty for assistance. China sent 2,500 troops. Japan, angered that it was not informed, dispatched its own forces. In 1895, 8,000 Japanese troops landed in Incheon, marched on Seoul, captured Emperor Gojong, and installed a pro-Japanese government.

Japan’s modernized army and navy, strengthened by the Meiji Reforms, dealt decisive blows to Qing forces. China sued for peace, signing a treaty that renounced its claims over Korea and paid a massive indemnity to Japan. Japan emerged as the dominant power in East Asia, positioning itself to control Korea.

Throughout the early to mid-twentieth century—and at other times in history—the Japanese Imperial House promoted the idea that Mimana (the Gaya Confederacy) had been a Japanese colony and that Koreans and Japanese shared a common ancestry. This narrative was used to legitimize Japan’s imperial conquest of Korea.

Emperor Gojong and his wife, Queen Min, were effectively trapped. Gojong sought assistance from China, while Queen Min turned to Russia. To counterbalance Japanese influence, she invited Russian advisors and investment. This move obstructed Japanese ambitions, and they resolved to eliminate her.

Under the direction of the Japanese ambassador, a plot was organized, and Queen Min was assassinated. Gojong was subdued, and Japan consolidated its control. Japan’s subsequent victory over Russia further cemented its dominance. The Eulsa Treaty reduced Korea to a Japanese protectorate, transferring many governmental, economic, and diplomatic powers to Japan. This led directly to Gojong’s forced abdication in 1907 and the formal annexation of Korea in 1910.

Colonial Rule and Resistance

Japanese colonization deeply scarred the Korean people, with consequences still visible in South Korea today. Reactions varied. Emperor Gojong was confined within the palace and repeatedly attempted to escape to establish a government-in-exile. He died in 1919 under suspicious circumstances.

His death sparked the March 1st Independence Movement. Religious and civic leaders issued a declaration demanding independence from Japan. The declaration was read publicly across the nation, igniting peaceful demonstrations. Protesters raised their hands and shouted “Mansei!”—meaning “ten thousand years” or “long live Korea.”

The demonstrations were nonviolent; the Japanese response was brutal. Police and troops beat and shot demonstrators, creating martyrs. The most famous was Yu Gwan-sun, a 16-year-old girl who became an icon of the movement. She was arrested, tortured, and died in Seodaemun Prison in Seoul.

Although the movement was crushed, it announced Korea’s demand for independence to the world. It later inspired Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance in India and Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights movement in the United States.

Resistance continued. A provisional government was established in Shanghai. Earlier, Korean patriot An Jung-geun assassinated Japanese Governor-General Ito Hirobumi. A devout Catholic and devoted son, An accepted his fate and was executed in Japanese-occupied China.

Armed resistance flourished in Manchuria and China, though not within Korea itself. After March 1st, Japan tightened its grip, pursuing full assimilation—turning Koreans into Japanese. The Korean language and surnames were banned, and Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese names.

Religion Under Occupation

The relationship between Christianity and the occupiers was complex. Most Protestant and Catholic churches were led by foreign missionaries whose teachings were Western and thus viewed as anti-Japanese. Japan imposed restrictions on church teachings, viewing the Old Testament as subversive because of its themes of liberation after suffering.

Some ministers were arrested, churches burned, and many Christians joined the resistance. Others cooperated, believing accommodation was the safer path. As part of assimilation efforts, Japan forced Koreans to worship at Shinto shrines. By 1925, all elementary students were required to bow at Shinto altars; by 1935, university students as well.

Some complied out of necessity; others resisted. Many Koreans turned to Christianity during this period. Some devout believers fled to remote areas, where they encountered remnants of shamanism. As often happens in history, beliefs blended. The result was a range of quasi-Christian movements later declared heretical.

These movements were generally rooted in native animism, layered with Taoist concepts and topped by varying messianic beliefs. Practices and ethics from Buddhism, Confucianism, and Christianity appeared in differing combinations.

One loosely connected movement was the Jesus Church Movement. They believed the Messiah would return as a man, born in Korea, and that the Fall of Man was sexual in nature, requiring sexual rites for restoration. These beliefs led to their condemnation as heretical.

After World War II, branches of these movements existed in both North and South Korea. The Israel Monastery led by Kim Baek-moon was well known. Moon Sun-myung was a member and disciple of Kim. They traveled together to Pyongyang in 1948 to meet others in the movement. Moon remained there until the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950.

War, Liberation, and Division

During World War II, Japan forced Koreans into labor in factories and mines under brutal conditions. Over 110,000 men were conscripted, and another 100,000 volunteered to fight for Japan. More than 50,000 were killed. American forces encountered and killed them as Japanese soldiers.

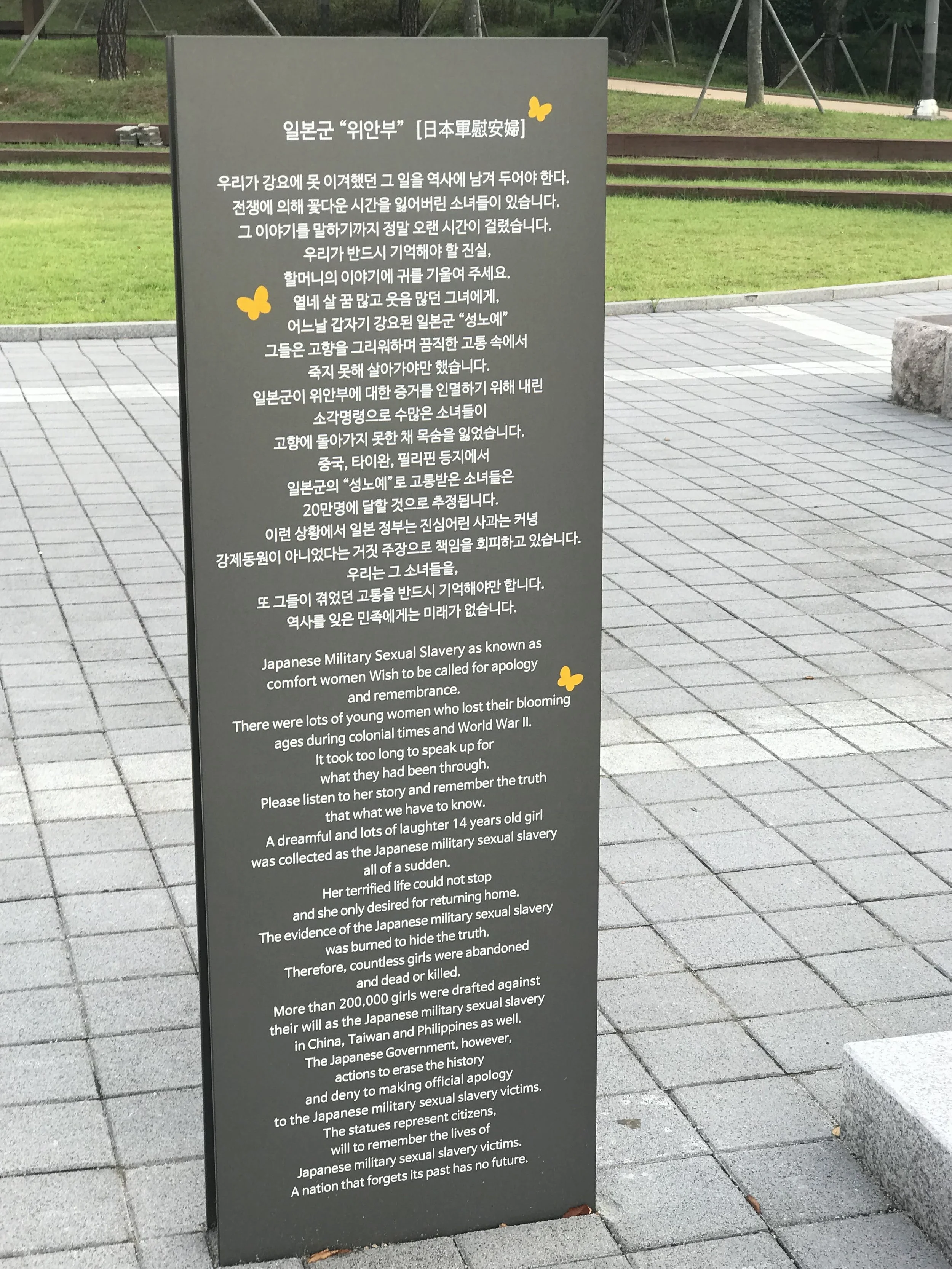

Japan also forced Korean women and girls into military brothels, mainly in China. Many were required to service dozens of men per day. A small number of these women are still alive today and protest weekly outside the Japanese Embassy in Seoul.

The Japanese army committed mass executions of Korean civilians in Korea, Manchuria, and Japan. The Japanese government has consistently minimized or denied these atrocities.

When the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war, Korea was liberated. Liberation Day is celebrated on August 15th. Koreans remembered who resisted, who collaborated, who lived, and who died. These memories shaped the postwar years.

Global politics dealt Korea a cruel blow. The United States accepted Japan’s surrender south of the 38th parallel, and the Soviet Union accepted it in the north. Japanese officials departed, but the U.S. military—unprepared and unfamiliar with Korea—retained many former Japanese administrators, causing deep resentment.

The U.S. refused to recognize the Shanghai-based Provisional Government led by Kim Gu and disbanded the popular People’s Republic of Korea. Refugees flooded south, and accusations of collaboration erupted. The left embraced Marxism; the right supported monarchy and elite privilege.

The issue was handed to the United Nations, which called for nationwide elections. Kim Il-sung refused participation in the North. Elections were held in the South under UN supervision, with a reported 95% turnout—the first time Koreans voted. Despite opposition from leaders like Kim Gu and a boycott in Jeju, a constitutional assembly was formed.

In August, it established 대한민국, the Republic of Korea. In the North, Kim Il-sung established the People’s Republic of Korea with Soviet backing, claiming authority over the entire peninsula.

The division was set—and the future looked dark.