History of Korea, Part 8

by Michael Downey

The Joseon Dynasty marked the beginning of modern-day Korea. At the same time, by adopting its name, it attempted to reach back to the original Old Joseon Dynasty for identity and legitimacy.

The founder of the new dynasty was General Yi Seong-gye (temple name Taejo). He had been sent by the last king of Goryeo to the north with an army to battle forces of the new Ming Dynasty. On the way, he changed his mind and turned back to overthrow the Goryeo regime. Angered by the government’s weakness and inefficiency, he took action. After several failed attempts to place someone else on the throne—attempts that ended in bloodshed—he ascended the throne himself.

At first, he was not inclined to make major changes and tried to maintain continuity. His new dynasty was largely dominated by the same ruling families and officials who had served the previous regime. However, succession issues among his sons and rivalries among factions quickly ended his reign. After six years on the throne, he abdicated in favor of one of his sons, went into semi-exile, and never saw any of his sons again.

During his short reign, he encouraged the people to identify as Korean again after the long hiatus under the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. He improved relations with the Chinese Ming Dynasty, and although he had fought against Japanese Wokou pirates, he also strengthened ties with Japan.

Confucianism vs. Buddhism

During the Joseon Dynasty, conflict between Neo-Confucianism and Buddhism reached a peak. Neo-Confucianism, developed in Song China, was based on traditional Confucianism but absorbed ideas of self-cultivation from Buddhism and concepts such as Ki (material force) from Taoism. While Neo-Confucianism emphasized duty and family obligations, Buddhism taught detachment from worldly ties—including family and social position—making the two natural rivals.

The new Joseon leadership admired Chinese culture and Confucian ideals. They envisioned a society built on order, duty, and moral cultivation. When founding the new capital, Seoul, King Yi Seong-gye brought both Buddhist and Neo-Confucian advisors. Buddhists were closely aligned with shamanism. A key question was where to place the western city wall. After much consultation, it was decided to exclude Mt. Inwang (인왕산 법 바위)—home to Buddhist and shamanistic shrines—from the city limits. This symbolically established Neo-Confucian supremacy and the persecution of Buddhism.

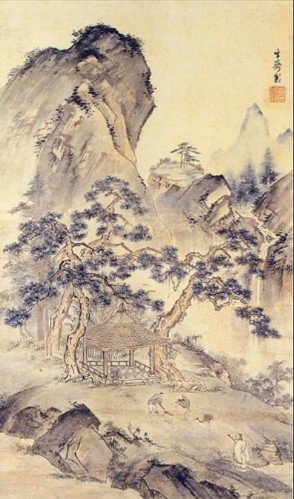

Buddhism was banned from the court, temple construction was restricted, Buddhist lands were confiscated, and limits were placed on the number of monks who could take vows. Under heavy pressure, Buddhism became more intertwined with shamanism, its followers increasingly came from lower classes, and temples moved deep into the mountains.

Social Classes in Joseon

Life for about 80% of the people remained much the same as in Goryeo. Most were farmers, fishermen, or merchants (sangmin). The nobi (slaves) increased in number, and several underclasses existed, including the baekjeong—hereditary butchers, leather workers, itinerant entertainers—and the kisaeng (기녀).

Kisaeng were enslaved women from outcast families trained as courtesans, skilled in music, dance, and poetry. Although of the lowest class, they played notable cultural roles. Their poetry—often about love, loss, and heartbreak—left deep marks on popular culture. Many themes in today’s Korean popular music reflect these roots.

photo credit: Michael Downey

King Sejong the Great

The most famous Joseon monarch was King Sejong, known as Sejong the Great. He ascended the throne at age 22 when his father (King Taejong) abdicated.

His greatest achievement was the creation of Hangul, the phonetic writing system of the Korean language. Before Hangul, Korean was written using Hanja—Chinese characters that were difficult to learn. Hangul made literacy accessible to ordinary people.

Sejong also sponsored scientific and technological advances, including rain gauges, sundials, water clocks, and celestial globes and maps. His curiosity and innovation greatly improved the lives of his people.

Political Factionalism

Throughout the Joseon era, political factions—regional and ideological—struggled for dominance. Succession disputes often led to fratricide and even matricide. Factionalism split elites into north–south and east–west power blocs, leaving the government unstable and often ineffective.

Imjin Wars (Japanese Invasions)

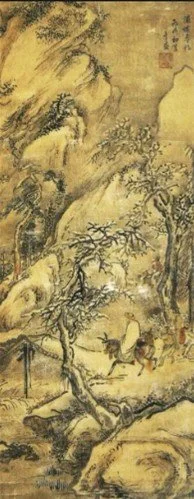

The Imjin Wars were invasions by Japan, whose main goal was to conquer Ming China, with Korea as the first step. Joseon was unprepared, and Japan captured Seoul and Pyongyang. Ming China provided military aid, and with the brilliant naval victories of Admiral Yi Sun-sin and his turtle ships, the Japanese were driven back.

A second invasion came in 1597, but this time Korea was ready and repelled it quickly.

Qing Invasion and Manchu Pressure

The Ming Dynasty struggled against Manchu Qing forces for a decade and was toppled in 1644. When Joseon supported Ming, the Qing invaded Korea in 1636, devastating northern and central regions. Cities were repeatedly pillaged, and Korea was forced to pay tribute. Still, Joseon elites regarded themselves as heirs of Ming civilization and rejected the “barbarian” Qing.

The first Europeans arrived during this era—a Spanish priest serving with Japanese troops and Dutch sailors shipwrecked on Jeju Island.

Isolationism and Christianity

After the Manchu invasions, conservative Neo-Confucian elites embraced strict isolationism. In the West, Korea became known as “The Hermit Kingdom.” Christianity entered via Qing China, brought by Jesuit missionaries. While Neo-Confucian elites rejected Christian ideas—especially the banning of ancestor worship—many of the lower classes embraced it with hope.

The government saw Christianity as a threat. Brutal persecutions followed, and over 20,000 native and foreign Catholics were martyred. Yet the religion survived and later flourished. Protestant missionaries, particularly from the United States and Britain, arrived later, building schools, hospitals, orphanages, and universities. The most famous was Horace G. Underwood, funded by the Underwood Typewriter fortune. Many Koreans today call Presbyterianism the “original church” of Korea.

East Meets West

The most important turning point in Asian modern history was the encounter between East and West. When Europeans arrived, all three major East Asian nations—China, Japan, and Korea—were in decline politically, socially, and economically. The industrialized West arrived with ships, guns, cannons, new ideologies, and new religions—claiming superiority.

This pressure triggered internal upheavals:

China: Taiping and Boxer Rebellions

Korea: Donghak (Dan Hak) Rebellion

Japan: Meiji Restoration

All were responses to Western imperialism and the collapse of traditional power structures. The Pacific War (World War II), the division of Korea, and the rise of Communist China were long-term results of this historic encounter.

Donghak – ‘Eastern Learning’

In the 19th century, Korea faced famine, oppressive taxes, corrupt politics, and ruling families that seized power through young puppet kings. Discontent grew across the country.

Many turned to religion. In 1860, Choe Je-u, a failed yangban scholar, founded Donghak (“Eastern Learning”) as a counter to Seohak (“Western Learning” — Roman Catholicism). Donghak blended Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, Shamanism, and Christianity. It was anti-dynasty, anti-landlord, and anti-foreign, appealing strongly to the lower classes.

Choe Je-u taught that God exists within each person, making each individual divine. His message of material and spiritual healing spread rapidly. Alarmed, the government executed Choe Je-u and 20 of his top followers in 1864, but his ideas lived on and sparked further uprisings.

The Donghak Peasant Rebellion (1894)

In 1894, Donghak followers raised a large peasant army in the southwest and defeated government troops. Seoul panicked and called on Ming China for help. Japan responded by sending its own army. The rebellion was crushed—but this sparked the First Sino-Japanese War, after which Japan expelled China from Korea and began 40 years of colonial rule (starting in 1905).