A History of Korea - Part 4

by Michael Downey

The early inhabitants of the Korean peninsula, by the weight of circumstances, were a violent and war like people. At the same time, they were deeply religious, keenly interested in their place within both the physical world around them and the unseen world beyond. From time immemorial, they conceived of this other world and developed beliefs and practices to interact with it. These spiritual traditions were brought with them from the distant reaches of Siberia and became known as Shamanism—or Mooism—in their own language.

At the center of these practices was the Moodang, or shaman. They believed in animism, totemism, and the spirit world, which was thought to permeate everything: mountains, rivers, sky, trees, tigers, bears—even grasshoppers. These spirits influenced all outcomes, good or bad. The Moodang served as the ultimate guide to the spirit world, able to perceive and communicate with spirits and enter their realm through trance. Since it was believed that disease and misfortune were caused by spirits, the Moodang was a witch doctor and healer. She became a master of medicinal plants and their uses. Because the future was believed to reside in the spirit world, the Moodang also became adept at divination. On the eve of critical decisions—like a tribal migration or a battle—a skilled Moodang was as valuable as gold. If her predictions proved accurate, she could rise in influence and even become close to the headman, chief, or king. Such a shaman might be called Mon'gun (Prince of Heaven).

In ancient Korea, there were religious figures called Mon'gun (天君,“Prince of Heaven”) who acted as intercessors for their people during great yearly ceremonies. These positions were often inherited and, in many cases, the Mon'gun also served as political leaders. There were also lesser shamans focused on curing disease and guiding the souls of the dead to the next world. These three functions—intercession, healing, and soul guidance—remain central concerns in modern Korean folk religion.

If a Moodang was wrong in her predictions or failed to deliver, she often faced severe consequences—sometimes death. It was a high-stakes role suited to spiritual gamblers. In the Siberian tradition, most Moodangs were women, though some men took on the role by cross-dressing and living as women. Moodangs believed they were chosen by an ambitious spirit. If a chosen individual rejected the call, they could suffer for days, weeks, months, or even years. The initiation into shamanism was symbolic of blood change—it was sexual, either literally or symbolically—making the Moodang the “wife of God.”

This form of shamanism was practiced unabated from the earliest Stone Age tribes through the era of the Three Kingdoms.

The Introduction of Buddhism and Chinese Thought

Buddhism was introduced into the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo in 372 CE by a monk named Sundo from the Chinese Qian Qin Dynasty. This marked the beginning of Buddhism’s significant influence on Korean society. China, being the dominant cultural force in the region, had advanced technology and ideas that could elevate the status of neighboring states. When the Chinese emperor sent a representative to Goguryeo, the Korean court paid close attention.

Unlike Christianity, Buddhism was not a jealous master demanding exclusive devotion. Instead, its practitioners lived by example and offered teachings without coercion. The leadership was impressed, and the people had little choice but to follow. However, Shamanism was not eliminated. It remained a practical and spiritual foundation for many, and in time, blended harmoniously with Buddhism.

The form of Buddhism that reached Goguryeo was already mixed with shamanism, shaped by its journey through northern China and Central Asia. Missionaries were adept at using occultism and magical practices to make Buddhism appealing.

Another cultural import from China was Confucianism, a philosophy emphasizing ethics and right relationships to foster a balanced society. It outlined the ideal roles between parents and children, siblings, rulers and citizens, and between king and nation. Filial piety, family loyalty, and civic duty were central to its teachings. This contrasted with Buddhism, which emphasized letting go of all attachments, including family. Naturally, Confucianism and Buddhism were ideological rivals.

Confucianism appealed to royalty and the ruling elite for its social order and practicality. Goguryeo even established a Confucian academy, the Tae Hak, in 372 to promote the philosophy. Meanwhile, Buddhism flourished among the general population, especially in mountainous monasteries. Confucianism held sway in cities, while Shamanism continued to thrive everywhere.

The Spread of Buddhism to Silla and Baekje

In 371 CE, the Silla Kingdom received Buddhism via a Chinese monk named Ado who was living in Goguryeo. This form of Buddhism had already been blended with shamanistic elements. While it took some time to gain traction in Silla, by 528 CE it was installed as the state religion.

The first Buddhist temple was constructed in 538 CE. Confucianism and Taoism also arrived, but their impact was minor compared to the continued dominance of Shamanism in everyday life.

Baekje, situated on the Han River and West Coast, was a maritime power that served as a cultural conduit between China and Japan. It played a critical role in transmitting syncretized Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and broader Chinese culture to Japan and South Asia. Baekje was largely responsible for the esoteric Buddhist traditions that shaped Japanese spiritual life.

In all three kingdoms, Buddhism took on an esoteric form that incorporated shamanistic rituals. Buddhist rites to protect the kingdom, cure diseases, and divine the future were deeply shamanistic in character.

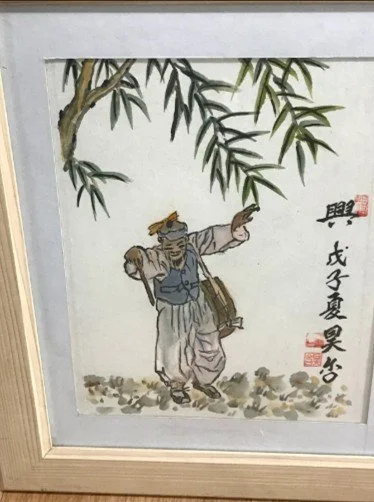

A Dragon, a Spirit, and a Dance

During the reign of King Hŏn’gang (875–886) of Silla, a thick mist enveloped the East Sea. An astronomer warned that the mist signified the arrival of a malevolent dragon. In response, the king performed a Buddhist ritual and vowed to build a temple. The mist cleared, and the dragon and his seven sons danced before the king. One of the sons, Ch’ŏyong, entered the capital city of Kyŏngju to serve the royal government. The king arranged his marriage to a beautiful woman.

One day, Ch’ŏyong returned home to find his wife sleeping under a coverlet with the spirit of smallpox. Instead of reacting with violence, Ch’ŏyong sang and danced. His calm response caused the spirit to beg for forgiveness and promise never to enter any home displaying Ch’ŏyong’s image. This gave rise to the custom of hanging Ch’ŏyong's portrait on doors to ward off illness.

This story illustrates the magical, mystical synergy between Buddhism and shamanism recorded in the Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms.

Esoteric Buddhism and Korean Culture

Inspired by esoteric Buddhist schools in China, Silla kings constructed elaborate mandala-shaped temples to create sacred spaces that would protect the kingdom. This idea of sacred space stemmed from Korean shamanism. Korean arts and culture are deeply rooted in these traditions. For example, Korean folk dancers emphasize breath—inhale and exhale—as the foundation of movement. Inhale (Ho) represents death or the abandonment of desires, while exhale (Heup) symbolizes revival and regeneration. This mirrors myths in which a hero becomes divine after undergoing suffering and rebirth.

Hand and foot movements in Korean dance also reflect this cycle of contraction (inhaling) and expansion (exhaling), symbolizing spiritual transformation.

Cultural Remains and the Hwarang

Two of the most famous sites reflecting the blend of Buddhism and Shamanism are located in Kyŏngju, the former Silla capital: Bulguksa (“Buddhist Nation Temple”) and the Sokkuram Grotto, a stone cave hermitage on T’oham Mountain.

The Hwarang ("Flowering Youth") were elite warrior bands established by the Silla king. According to the Samguk Yusa (Three Kingdoms History), boys from noble families were selected for their beauty and virtue. They were the successors to earlier women’s groups called Wonhwa (“Original Flowers”) who had been devoted to the arts. These young men became the spiritual and military backbone of the Silla kingdom.

There was a close relationship between the Hwarang and Buddhism, which had been accepted by the Silla elite. Buddhist monks mentored the Hwarang in both physical training and spiritual development. Monks taught martial arts for self-defense during pilgrimages and shared meditation practices. Both monks and Hwarang undertook pilgrimages to sacred mountains, seeking spiritual enlightenment and supernatural encounters.

Unification

The struggle among the three kingdoms persisted until Silla, with the aid of the Chinese Tang Dynasty, overcame its rivals and formed the Unified Silla Kingdom.

photo credit: Michael Downey