A History of Korea, Part 10

All photos submitted by M. Downey

By Michael Downey

The first president of the Republic of Korea was Syngman Rhee. Rhee was born into an upper-class family during the Joseon Dynasty. He received a traditional Confucian education and later attended a Methodist high school, where he converted to Christianity. From a young age, he demonstrated leadership potential, becoming the head of several civic and literary clubs during his school years.

By the time Rhee graduated, Japan had established a pro-Japanese government in Seoul. Rhee joined the resistance movement and was imprisoned for his activities. After his release, he emigrated to the United States, where he dedicated himself to the Korean independence cause. He came to believe that the United States offered the best chance to liberate Korea from Japanese rule.

Rhee actively organized within the Korean diaspora, building networks and lobbying American political leaders. He met with many U.S. politicians, including Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, to raise awareness of Korea’s plight. He also raised funds and supported himself through literary and educational work. After a brief return to Korea to assess conditions, he relocated to Hawaii.

Following the failure of the March 1st Independence Movement, various resistance leaders formed the Provisional Korean Government (PKG) in Shanghai, China. Although Rhee was still in the United States, he was elected president of the government in exile and served for about six years. For more than two decades, the PKG functioned as Korea’s voice for independence, constantly relocating to evade Japanese military police.

Over time, ideological divisions fractured the leadership. Kim Gu aligned with right-wing Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, while Premier Yi Dong-nyeon began accepting assistance from Soviet agents operating in Manchuria and shifted leftward. Rhee remained firmly committed to American sponsorship. By 1925, Rhee was impeached and forced out, and the PKG gradually lost influence.

After Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II, many leaders, including Rhee, returned to Korea, formed political parties, and competed for power. Rhee’s English fluency and pro-American stance made him appealing to the U.S. military government. His marriage to a Caucasian woman further distinguished him. He was effectively assured election as the first president by the newly formed National Assembly.

Despite his credentials, Rhee appeared disconnected from popular sentiment. His leadership relied heavily on American backing rather than grassroots support.

Meanwhile, in the North, Kim Il Sung, a Soviet-backed anti-Japanese guerrilla leader and founder of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, consolidated power. Although initially aligned with Marxism-Leninism, Kim developed his own ideology known as Juche, meaning self-reliance. His ultimate ambition was to reunify the Korean Peninsula under his rule—an impossible task without Chinese and Soviet support.

After Mao Zedong’s victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949, Kim’s prospects improved. Mao sought global communist dominance, with the Soviet Union as sponsor, but Joseph Stalin as both ally and rival. As Mao lobbied for Soviet military support, Kim likewise sought backing for his invasion plans.

Between 1945 and 1948, the Soviet Union poured money, technology, and expertise into North Korea to counter American influence in the South. In the spring of 1949, Kim traveled by train through Siberia to Moscow to secure Stalin’s approval. Stalin, cautious due to tensions with the United States, offered tacit consent—“a nod is as good as a wink to a blind horse.” Kim returned to Korea prepared to act.

Communist unrest was not limited to the North. Anti-government and anti-yangban sentiment was widespread in the South, particularly among those returning from Manchuria and China who had been exposed to Marxist-Leninist ideology. Under President Rhee, conservative forces adopted a harsh policy toward leftists, communists, and suspected sympathizers.

On Jeju Island, tensions between police and civilians erupted when police fired into a crowd, killing six people. A general strike followed, supported by the Workers’ Party of South Korea. Armed rebellion ensued, aimed at provoking a violent response and disrupting upcoming elections under the American military government.

Right-wing youth groups were sent to Jeju, where widespread abuse of civilians occurred. In October 1948, Rhee ordered the eradication of all communists and traitors on the island. Villages more than five kilometers from the coast were burned, paramilitary forces carried out mass executions, and bodies were dumped into the sea. An estimated 15,000 to 30,000 civilians were killed. Many survivors were imprisoned and later disappeared during the 1950 war.

While anti-communist violence was not uncommon globally at the time, the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians can never be justified.

On June 25, 1950, Kim Il Sung launched a full-scale invasion of South Korea. The South Korean army, caught by surprise, collapsed quickly, and Seoul fell within three days.

The international community suspected Soviet and Chinese backing and brought the issue before the United Nations Security Council. At the time, the Soviet Union was boycotting the council over the refusal to seat the People’s Republic of China instead of Taiwan. This absence allowed the council to authorize military action. A UN force, led by the United States, was dispatched to aid South Korea.

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Powers in Asia, was appointed commander of UN forces. Sixteen nations contributed troops, medical personnel, or supplies, though the United States bore the overwhelming burden of manpower, resources, and casualties.

While some American soldiers behaved poorly, the vast majority served honorably. They are heroes deserving of respect.

About ten years ago, my wife and I visited the UN Cemetery in Busan. The memorial walls list the fallen from each participating nation. Some countries had only a handful of names; the United Kingdom had several thousand. The American section required seven walls to display the names of more than 38,000 dead.

We spent three hours there, touching every name. I wept openly. Those names represent the greatest treasure of my country—young men who often did not even know where Korea was, yet gave their lives defending it.

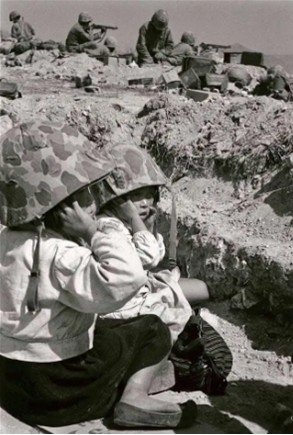

During the bleak summer of 1950, UN forces were pushed into a defensive perimeter around Busan. Reinforcements arrived, including the re-formed First Marine Division, veterans of Guadalcanal, Peleliu, and Okinawa.

In September 1950, MacArthur executed a bold amphibious landing at Incheon. On September 15, Marines stormed Green, Red, and Blue Beaches, overcame extreme tidal conditions, scaled seawalls, and defeated North Korean defenders. Within two weeks, Seoul was liberated, supply lines severed, and Busan relieved.

UN forces advanced northward. By mid-October, X Corps captured Heungnam, liberating prisoners including Sun Myung Moon. Troops believed they would be “home for Christmas.”

At Chosin Reservoir (Lake Changjin), Chinese forces intervened. Mao committed 120,000 troops of the People’s Volunteer Army, surrounding 30,000 UN troops, including 25,000 Marines. In the coldest winter in a century, the Chinese demanded surrender.

Instead, the Marines advanced. Over 13 days, they fought their way to Heungnam under constant attack, carrying their wounded, recovering most of their dead, and saving much of their equipment. More than 20 Chinese divisions were destroyed.

The breakout from Chosin is regarded as one of the greatest feats in American military history. X Corps evacuated by sea and returned to Busan to continue the fight.